The Nationalism in National Security

On the stories nations tell, the policies they produce, and the consequences for power, ethics, and civil liberties.

Editor’s Note

This essay examines how nationalism increasingly shapes the architecture of U.S. national security, not only as an identity claim but as a strategic driver of industrial policy, economic statecraft, and geopolitical interpretation. By tracing how subjective narratives harden into objective policy, it highlights the dynamics through which perception, volatility, and power projection influence both domestic politics and international markets. This is not a forecast, but an inquiry into the conceptual frameworks guiding U.S. security thinking in a rapidly shifting world — and an invitation to reassess how threats are constructed, how they mobilize institutions, and how they shape the future of American strategy.

Synopsis

This essay explores how nationalism increasingly shapes the foundations of U.S. national security, transforming subjective narratives into institutional policy. It argues that the modern security landscape is defined less by objective threats and more by the interpretations that political actors, markets, and media attach to moments of crisis. Through the lenses of industrial policy, economic statecraft, information volatility, and geopolitical realignment, the piece examines how states construct threats, mobilize power, and react to shifting global dynamics. Ultimately, it asks readers to reconsider how the United States defines danger—and how those definitions shape both domestic stability and international strategy.

Narrative as the Foundation of Policy

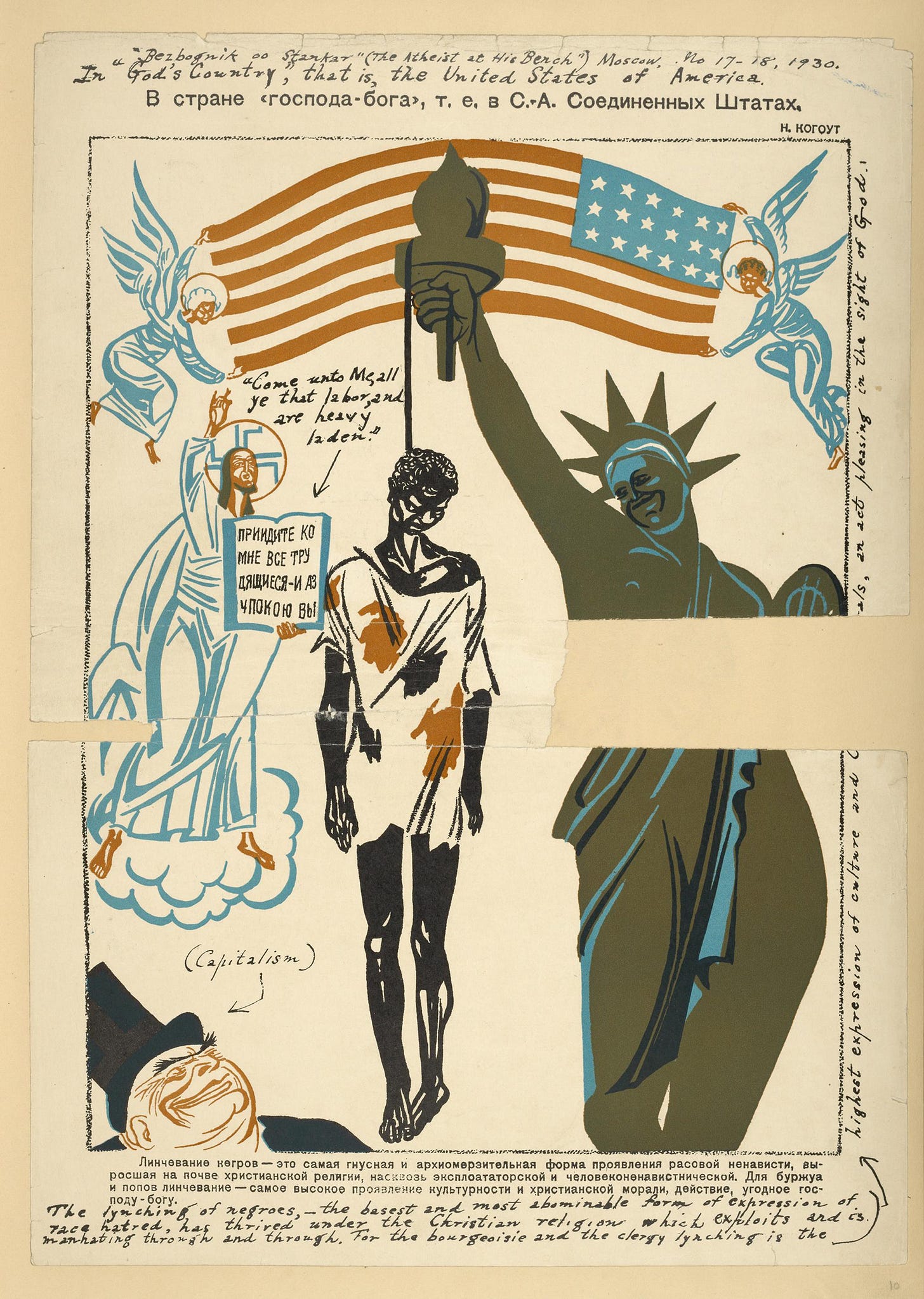

“In ‘God’s Country,’ That Is, the United States of America,” Nikolai Nikolaevich Kogout, 1930.

Soviet anti-American and anti-religious propaganda illustration published in Bezbozhnik u stanka (“The Godless at the Workbench”) by the League of Militant Atheists, using the image of a lynched Black American at the Statue of Liberty to indict U.S. racism and Christian hypocrisy during the early Cold War era.

Academics like to say the modern world is filled with -isms, usually to emphasize their subjectivity. Nationalism may be subjective, but national security is treated as objective.

Policymaking starts with narratives — identity, fear, aspiration — and ends with institutional action. Threats are defined, strategies are built, and institutions execute. But the boundary between foreign and domestic is thin. Domestic narratives about a “foreign enemy” can shape national security logic long before concrete policy emerges.

Once a narrative gains momentum, escalation becomes politically effortless.

Nationalism and the Architecture of Threat

Security is filtered through worldviews that blend academic justification with prejudice. Entire groups can be monitored, constrained, or securitized based on race, religion, or nationality.

National security is not just a bureaucratic domain — it is an imagination. It encodes what a society believes is dangerous, and what it believes is worth defending.

Industrial Policy and the New Security Economy

For decades, U.S. national security priorities revolved around the Middle East. But heading into 2026, the Trump White House reframes Europe—not Russia—as the primary strategic concern.

This is nationalism expressed as industrial policy: using tariffs, subsidies, and coercive economic tools to pull industry back into the domestic sphere.

This shift signals the rise of economic statecraft — weaponizing industrial capacity in interstate competition.

Economic statecraft generates political volatility, which spills into markets. Volatility unfolds in two phases:

the delayed reaction to a major event

the interpretations that crystallize in that window

Information warfare thrives in these moments. Social media saturates instantly; corporate media saturates days later; markets react fastest of all.

The mismatched speeds create strategic openings.

Power Projection and Political Volatility

Consider U.S. policy toward Venezuela.

Washington doesn’t enter a tit-for-tat; it simply tats — deploying a strike carrier, projecting force, dropping bombs. Venezuela has no conventional capacity to respond. U.S. power projection creates political volatility inside Venezuela, shaping elite reactions and public perceptions of legitimacy.

The U.S. has no appetite for a guerrilla war. Maduro — facing foreign loans, internal repression, and geopolitical pressure — has little choice but to negotiate.

The Four Pillars of Industrial Security

Industrial policy expresses itself through four levers:

Export controls

Tariffs

Subsidies

Nationalization

Tariffs illustrate the dynamic vividly.

On “Liberation Day,” Trump floated an invented tariff figure. Markets plunged when they opened — then soared after one erroneous tweet claimed a “90-day halt” was coming. The largest single-day swing in decades came from an information distortion, not actual policy.

Subjective perception moved objective markets.

Foreign actors understand this interplay. Their interests — FDI, loans, private-sector partnerships — can be framed as aligned or adversarial, shaping public support. Which raises a question:

Why do U.S. policymakers still rely on Cold War–era security architectures for a Middle East that has fundamentally changed?

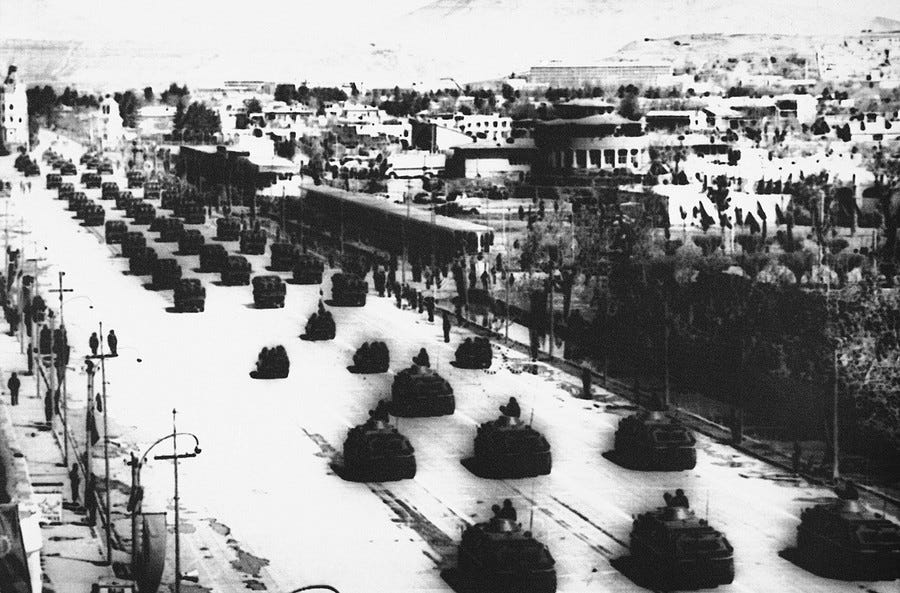

Afghanistan and the Long Arc of Sovereignty

The 1979 Afghan Revolution — when the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan overthrew President Daoud Khan — initiated a 45-year struggle over sovereignty. The new Marxist-Leninist government aligned with the Soviet Union, triggering foreign intervention and domestic resistance.

But today:

Afghanistan is more neutral toward Russia

The U.S. is more neutral toward Russia

Saudi Arabia no longer exports ideological militants into proxy wars

The geopolitical logic of the region has shifted. The old security maps no longer match the terrain.

Contentious Politics and the Security Imagination

A stable state requires that its people believe they control their collective destiny. When governments rely on coercive tools, the deeper issue is not security — but legitimacy.

These fractures generate the conditions for contentious politics in the Tilly sense. Political entrepreneurs elevate grievances into public conflicts, shaping narratives through rhetoric, research, activism, media, and cross-border influence.

Foreign actors can shape these discourses too. Once foreign pressure points enter the national security imagination, they become potential threats — whether material or merely perceived.

Conclusion: Security, Narrative, and the Ethics That Hold a Nation Together

National security is never just about external threats; it is a strategic architecture built from the narratives a nation tells itself. When nationalism becomes the lens, safeguarding the nation and projecting power outward blur into the same instinct. Industrial policy becomes a competitive weapon, perception becomes coercion, and volatility becomes the terrain where markets, governments, and foreign actors operate.

Yet beneath this is a philosophical truth: a state that cannot resolve its internal tensions — legitimacy, identity, sovereignty, civil liberties — will externalize those struggles into its foreign policy. Threats are not only assessed; they are constructed. And once constructed, they justify reshaping economies, disciplining populations, and hardening institutions under the banner of stability.

Power today depends less on military scale and more on the ability to define meaning in moments of crisis. Outdated security architectures distort how states interpret emerging realities. Nations that will define the next era are those able to see how subjective narratives drive objective policy — and how economic statecraft, political volatility, foreign influence, ethics, and civil liberties intersect.

The task ahead is not merely protecting the nation, but understanding the stories that animate its fears — and ensuring those stories do not become the very threats they claim to guard against.

Final Takeaway

The strength of a national security system is measured not only by its ability to manage threats, but by its ability to protect ethics and civil liberties while doing so.

About the Author

Christopher Sweat is a researcher and media strategist focused on political risk, conflict environments, and the shifting architecture of U.S. national security. His work blends field documentation with analysis of industrial policy, information warfare, and state-society dynamics. As the founder of GrayStak, he produces real-time insights into protest movements, political volatility, and geopolitical realignments. His reporting has reached millions and informed conversations across activist, academic, and policy networks.

Brilliant piece on the narrative architecture of security policy. Your framing of the tariff volatility example really exposes the feedback loop betwen perception and material outcomes in ways most security analysis just glosses over. If subjective interpretations can move markets that dramatically, then the entire distinction between imagined threats and real threats starts to collapes operationally. The Afghanistan point is especially sharp, we're still applying a Cold War threat map to a region where the actual incentive structures have completely shifted.