Martial Law in Seoul, Martial Law in Washington?

South Korea stopped a coup before sunrise. In the U.S., slim margins and gridlock could make reversal impossible.

Editor’s Note

On December 3, 2024, South Korea’s president declared martial law. By dawn, it was gone. Within months, he was impeached, removed, and jailed.

This is not a distant story. For Americans, it is a warning. The United States does not have South Korea’s speed, nor its democratic reflexes. If martial law were invoked here, our institutions would move slowly, our partisanship would paralyze response, and our coercive agencies would enforce “order” while Congress argued.

For markets, the lesson is stark: political violence is financial violence. And for activists, it is sharper still: democracy is not self-sustaining. It has to be defended — in the streets, in the courts, in the chambers — all at once.

A Six-Hour Coup

On the night of December 3, 2024, President Yoon Suk-yeol appeared on television. His tone was severe, almost brittle. He accused the opposition Democratic Party of conspiring with North Korea to destabilize the state. Then, in a sentence that froze the nation, he declared martial law.

It was the first such decree since the late 1970s. Armored vehicles were ordered into Seoul. Military units received instructions to secure communication nodes. South Koreans who had grown up believing their democracy was durable suddenly found themselves staring at a nightmare from their parents’ generation.

But the collapse never came. Within the hour, the National Assembly convened an emergency midnight session. Lawmakers declared the decree void. By dawn, the Cabinet, reading the political landscape, formally repealed it. What could have been an authoritarian takeover lasted just six hours.

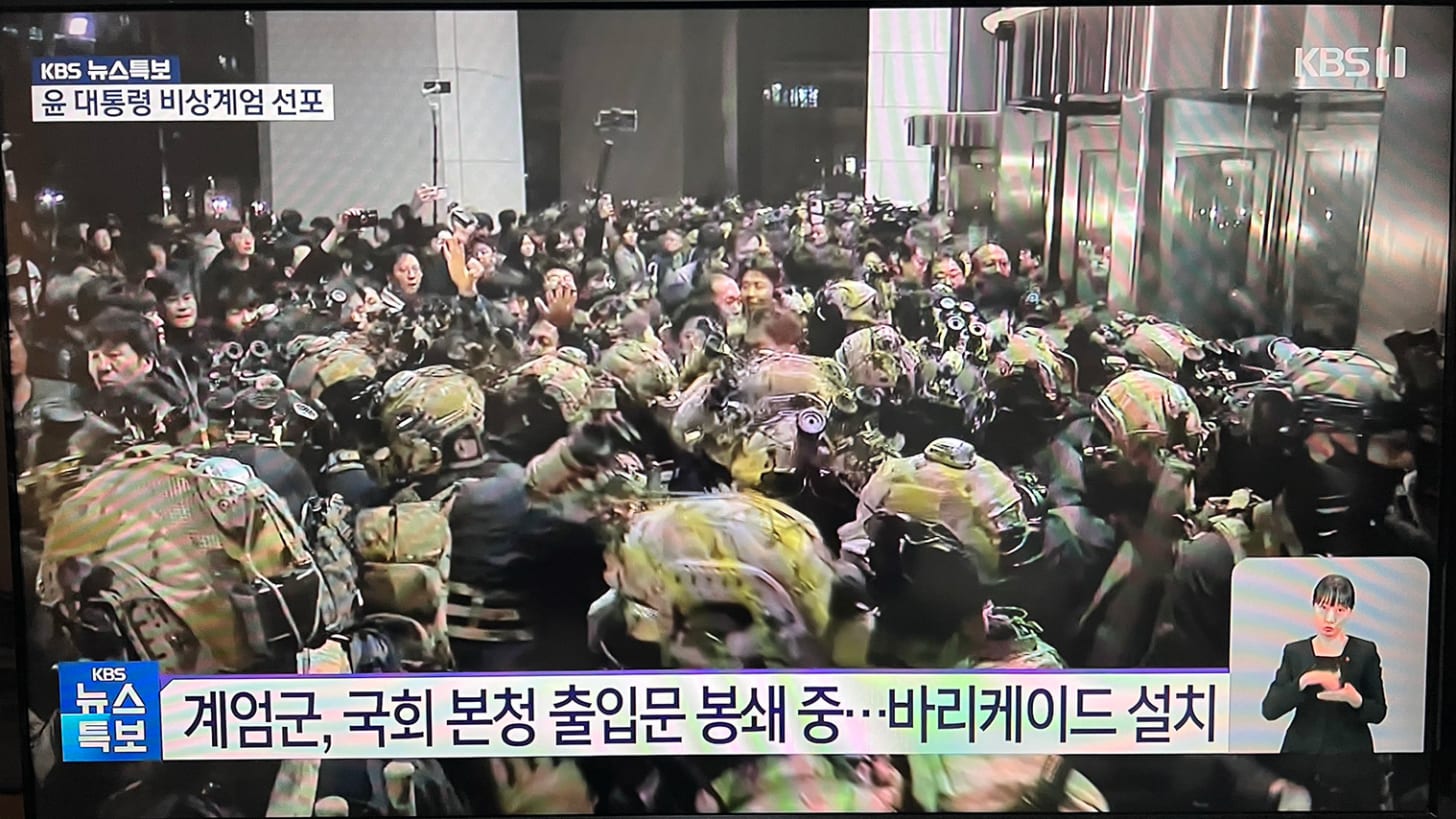

Pictures from the Scene

Below, a sequence of images captures how citizens mobilized to reclaim democracy — and how lightning-fast action by institutions cemented the reversal.

Within the hour, the National Assembly convened an emergency midnight session. Lawmakers declared the decree void.

Outside, the streets filled. What follows is a visual record of how democracy held the line: lawmakers inside, the public outside, and soldiers facing human barricades.

1. Protesters Demand Resignation

AFP / Jung Yeon-je, via Al Jazeera

Protesters held placards demanding President Yoon resign, massed outside the National Assembly as martial law was declared

2. Seoul’s Streets at Night

AFP via Foreign Policy

Tens of thousands flood downtown Seoul, blocking major intersections, a show of unified resistance against martial law.

3. Standing Against Military Vehicles

Reuters via People’s Dispatch

Military vehicles roll toward the National Assembly — only to be met by crowds forming human barricades in defense of the legislature.

4. Bodies as Barricades

Getty Images via RFA/Stanford

Inside and outside the Assembly building, protesters clash with police. Their bodies become the barricade that democracy itself rests upon.

The Chain of Events

The rapid reversal did not end the crisis. Instead, it triggered a cascade:

December 4–7: Protesters filled the streets around the Assembly, making it impossible for lawmakers to ignore the public’s demand for democratic order.

December 7: An initial impeachment vote failed when ruling-party members boycotted.

December 14: A second vote succeeded, 204–85. Yoon was suspended.

April 4, 2025: The Constitutional Court ruled 8–0 to uphold impeachment, permanently removing him from office.

June 3, 2025: Opposition leader Lee Jae-myung won the snap election.

Summer 2025: Yoon was arrested for insurrection, and his wife was jailed on corruption charges. For the first time in South Korean history, a presidential couple sat behind bars together.

South Korea had faced a coup attempt and defeated it — not through the army’s restraint, nor international intervention, but through a combination of institutions willing to act and people willing to stand in the streets.

The American Comparison

When Americans read this, many instinctively think of Donald Trump. The parallels are easy: both men thrive on painting their opponents as enemies of the state, both cultivate loyalty from hard-right bases, and both see institutions not as checks but as obstacles.

But structurally, the United States is more fragile than South Korea. Seoul’s Assembly acted overnight. In Washington, the process would take weeks. Repeal legislation would have to crawl through the House and Senate, both chambers bitterly divided, and even if it passed, the president could veto it. Overriding that veto would require two-thirds in both chambers — a political impossibility in today’s polarized climate.

South Korea impeached Yoon in less than two weeks. America’s impeachments drag on for months, often serving as a spectacle rather than a solution. And where South Korea’s military refused to enforce Yoon’s order, America’s federal enforcement agencies — ICE, DHS, HSI — already operate with paramilitary swagger. They would not hesitate to police dissent under a president’s emergency order.

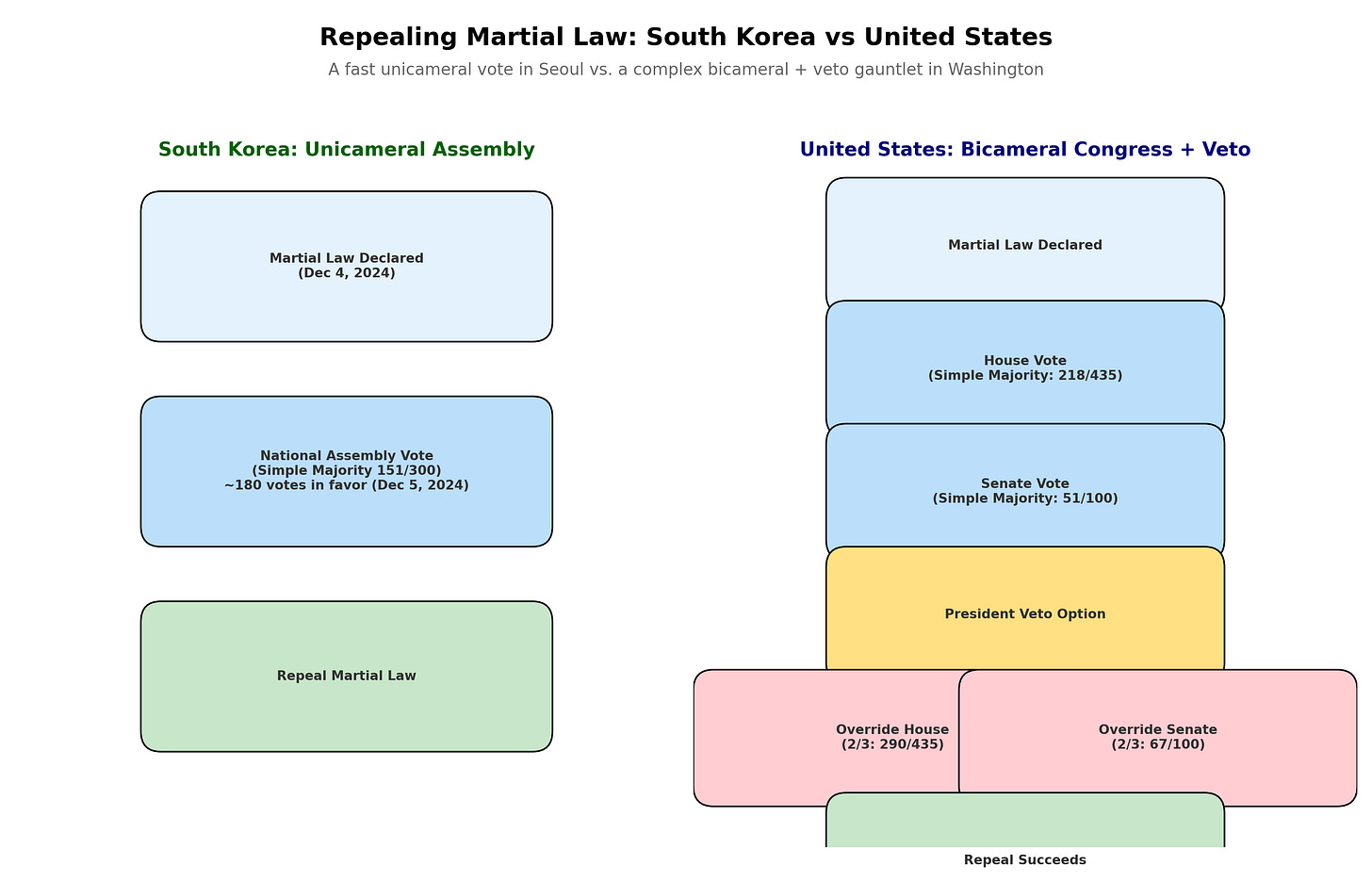

Unicameral vs. Bicameral: Why Speed Saved Korea

The difference is structural as much as cultural. South Korea has a unicameral legislature: one chamber, one vote, one night. That speed was decisive.

The United States has a bicameral Congress, and in a crisis, that design could be fatal to democracy. In the House, Trump’s slim Republican majority heading into the midterms would likely ensure that any repeal bill died on arrival. In the Senate, even if a bill passed, the filibuster would block it. And if, against all odds, both chambers passed repeal, the president could veto it. To override, Congress would need 290 votes in the House and 67 in the Senate — numbers beyond reach.

In Seoul, martial law collapsed in six hours. In Washington, it could stretch on for months. For markets, that delay means prolonged volatility, capital flight, and collapsing investor confidence. For activists, it means the battle is not an overnight mobilization but a protracted siege.

How to Read This Chart

South Korea’s National Assembly is unicameral — a single chamber where a simple majority (151 of 300) can reverse martial law. In December 2024, lawmakers exceeded that threshold with ~180 votes, repealing President Yoon’s order in just one day.

By contrast, the United States has a bicameral system. Even if the House and Senate both voted to end martial law with simple majorities, a president could veto the bill. Overriding that veto would then require two-thirds majorities in both chambers — 290 in the House and 67 in the Senate. In today’s polarized Congress, reaching those numbers would be nearly impossible.

Why This Matters

The chart makes clear that in South Korea, institutional design allowed for a swift rollback of martial law — a single chamber and a simple majority vote. In the United States, the bar is almost impossibly high. Even if martial law were broadly opposed, a president could veto any repeal effort, forcing Congress to deliver two-thirds supermajorities in both chambers. Given polarization and gridlock, that’s a fantasy scenario.

That leaves one real safeguard: elections. If a president inclined toward authoritarian tactics enters office with a supportive Congress, martial law could be entrenched for far longer than Americans imagine. The only buffer is a Democratic (or at least anti-authoritarian) majority at the ballot box. Midterms matter not just for budgets or judges, but as a brake on emergency powers.

Global Reaction

South Korea’s allies responded immediately. Washington expressed “grave concern,” Tokyo called the decree destabilizing, and Brussels urged restraint. But these statements were mainly symbolic. No ally could undo martial law for South Korea. Only South Korea could.

The Assembly’s quick repeal reassured allies. If martial law had been declared, Northeast Asia could have become unstable, and the U.S.–Korea alliance might have faced a crisis. The world was reminded: democratic allies can celebrate and warn, but when a democracy’s leader turns against it, only its institutions and people can stand against it.

Historical Parallel: The Shadow of 1979

The speed of 2024 can make it seem inevitable. It was not. South Korea has been here before. In 1979, General Chun Doo-hwan declared martial law after the assassination of President Park Chung-hee; that decree held for months, culminating in the Gwangju Uprising, where hundreds were killed.

What took six hours in 2024 lasted half a year in 1979. The difference wasn't in the decree but in the country: a more mature democracy, an organized public, and institutions unwilling to be bullied.

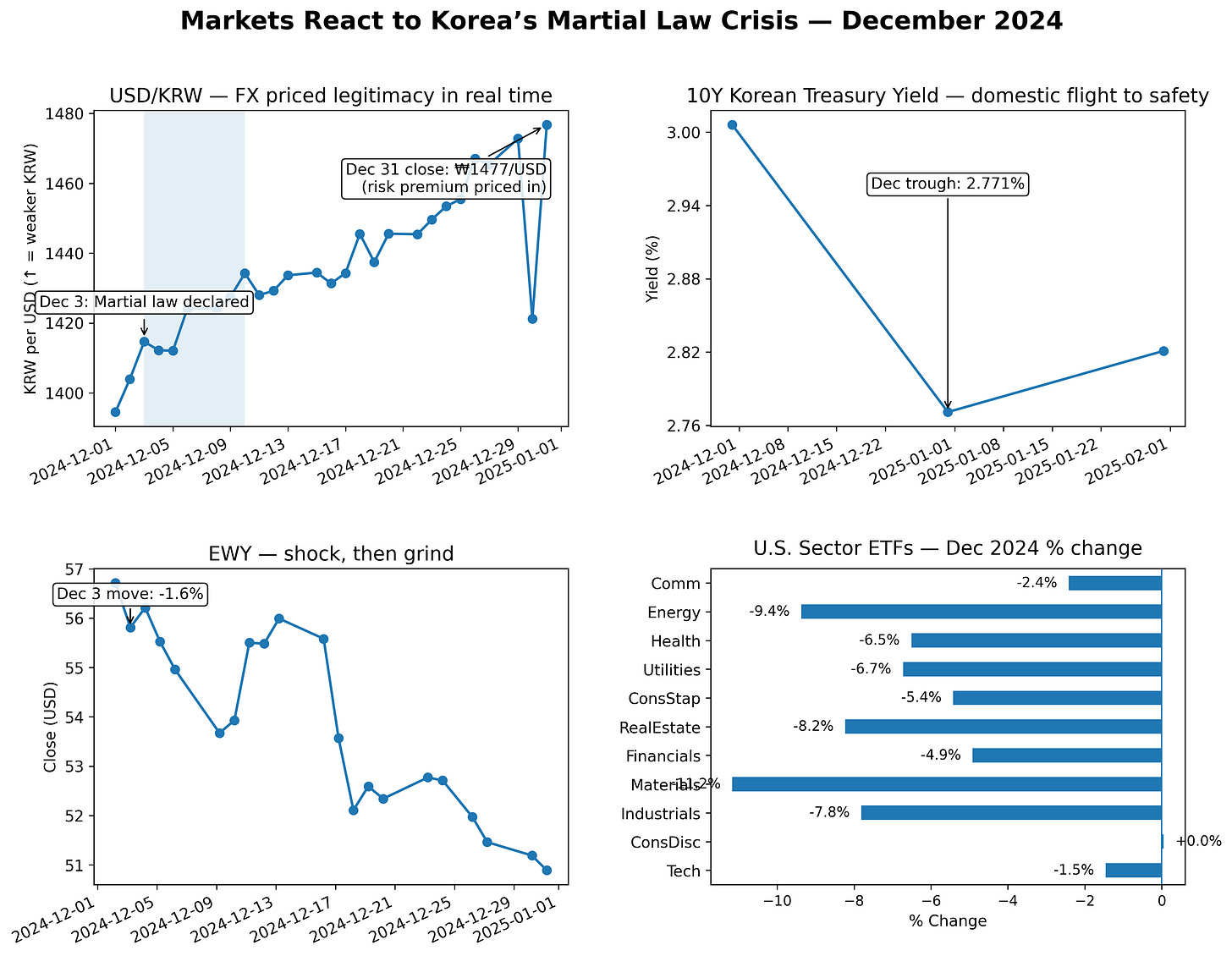

Markets: How Money Priced the Coup

Markets recognized what was unfolding earlier than many observers. They priced legitimacy in real time. The won weakened step by step — ₩1,403.7 on December 3, ₩1,428.2 by December 10, and ₩1,478.3 by year’s end. This was not a macro slide but a rule-of-law risk premium.

Domestic investors fled into sovereign paper, pushing the 10-year KTB yield down from 3.006% in November to 2.771% in December. Equities traced a different arc: the EWY Korea ETF fell 3.8% on the day of the declaration, then ground sideways, as traders wagered the constitution would ultimately hold. Still, it could not price the cost of getting there.

Sector moves told the same story in miniature. Banks sold off, semiconductors flinched, defense names rallied briefly, and shipping and energy braced for strikes at ports. Volatility spiked and then faded, mirroring the trajectory from panic to resolution.

Every chart told the same story: when politics destabilizes, capital flees.

Figure above. Financial markets immediately repriced Korean risk after the December 3 martial law declaration, with the won sliding and equities and sector groups diverging. The moves reflect how quickly capital translated political disruption into a legitimacy premium.

Voices From the Street

One protester outside the Assembly told reporters: “If we left it to the politicians, Yoon would still be in power this morning.”

A labor organizer put it more bluntly: “The Assembly needed legitimacy, and we gave it to them. Our bodies in the street forced their hand.”

These voices remind us that markets respond to risk, but people generate legitimacy. Without those crowds, the Assembly’s midnight vote might never have happened.

Lessons for Activists and Allocators

For activists, the lesson is clear: time is a strategic tool. In Korea, protests shortened the institutional timeline, pushing lawmakers to act before dawn. In the U.S., with its bicameral disagreements and veto power, timelines tend to stretch out. Activism becomes not a quick race but a prolonged siege — requiring legal funds, security measures, and media strategies to sustain the effort over the long term.

For allocators, the lesson is equally stark: political risk is no longer an outlier. Buy the domestic duration dip, fade the FX spike, rotate out of banks and into defense, and budget more for hedging. When legitimacy wavers, every asset class reprices.

Markets Glossary (For the Rest of Us)

Fade the FX spike — When a currency suddenly surges, like the Korean won after the repeal of martial law, traders may “fade” it: betting that the spike is temporary and will soon reverse.

Bond yields — The return investors seek when lending money to governments or companies. Higher yields mean higher perceived risk. When yields spike during a crisis, it signals that markets are anxious about instability.

Credit spreads — The difference between “safe” government bond yields and riskier corporate debt. Widening spreads mean investors see higher default risk.

Volatility index (VIX) — Known as Wall Street’s “fear gauge,” it rises when markets anticipate turbulence. Think of it as a seismograph for financial panic.

Sector ETFs — Exchange-traded funds that group stocks by industry (such as defense, energy, or tech). Monitoring their performance reveals which industries benefit or suffer from political shocks.

Closing Argument

Markets can measure risk, but they cannot secure legitimacy. In Seoul, traders responded faster than diplomats or generals, selling the won and piling into sovereign bonds as martial law rippled across the system. The message was unmistakable: capital abhors uncertainty, and political drama is not abstract — it has a price.

Yet markets only price the contours of disruption. They can record fear, but not resolve it. Legitimacy is ultimately contested in the streets, legislatures, and courtrooms — in places where traders cannot intervene. South Korea proved that institutions, backed by civil society, could halt a coup before dawn. In Washington, where polarization and procedural gridlock leave vulnerabilities exposed, the outcome may not be as swift.

For Wall Street, the lesson is vigilance; for policymakers, it is urgency; for activists, it is a reminder that pressure from below matters. Money may move first, but it cannot defend democracy alone. That responsibility remains with people and institutions willing to bear the cost of holding the line.

Christopher Sweat is the founder and CEO of GrayStak Media, a political risk and intelligence firm that blends on-the-ground reporting with market analysis. Based in Chicago and Washington, D.C., he covers how protests, policy fights, and legitimacy crises ripple through financial markets and political institutions. His work spans audiences from Wall Street to grassroots movements, drawing connections between capital flows, state power, and community resistance. Sweat previously ran for U.S. Congress and holds a degree in political science from the University of Colorado Boulder, with a focus on international security and political economy.

thank you for useful insights, however it seems there is a large area missing

please can you do a followup piece outlining the roles, logistics and actions of press and media institutions and operations throughout such crisis cycles in both countries respectively ?